Unlike most “content writers,” I really do get asked about bicycle buying recommendations on a daily basis. After having written about road bicycle buying, it’s time for advice on buying a mountain bicycle (MTB from now on).

In a separate article I’ve explained how to ask for bicycle buying help/advice?

For my default product review stance and philosophy, see:

Products and reviews – CAUTION!

TL/DR

The idea of this article is to explain everything related to buying a MTB:

- MTB types (and what each is best for).

- Pros and cons of different equipment classes and types.

- What to look for and expect in each price range?

- How to pick the right size?

The article is long, but I made a table of contents, so you can “skip” to the parts of interest – including the concrete buying recommendations (with explanations why I recommend those).

1. Introduction

I am writing this for the most part for selfish reasons – so when people ask me for the 1000th time, I’m able to just give them a link to this article. 🙂

I’ll explain what to look (out) for, so you can assess each particular bicycle model by yourself, not just take my advice “blindly.” After all, not every model is available everywhere, and no one knows your priorities and taste better than you.

Briefly: bicycle make is less important – what matters is the frame and component quality, and that you buy the right bicycle size.

I also advise you to read my short buying guide, before reading this article. It’s called: Which bicycle should I buy?

There I briefly explained the basics.

Of course, if you don’t feel like learning all the technical details, you can just go to the T.O.C. and skip to the part where I give the MTB buying recommendations.

Note: I’m not selling bikes. No bicycle links in this article are affiliate links. All that I wrote here is my opinion, based on my knowledge and experience.

For writing this article, I have consulted with Miloš Radosavljević – an avid MTB cyclist and an experienced mechanic currently working with Vector Bikes from Novi Sad.

Update 2024:

Miloš has started his own “Bike Team” bicycle shop.

He’s also the author of the Instagram profile Garijeva Garaža.

Miloš has taken the time to read the article, correct any mistakes, and share his thoughts.

Many thanks for the devoted time and effort.

2. What is a mountain bicycle (MTB)?

MTB stands for MounTain Bike. It is a bicycle designed for easier riding off-road – on trails, mud, dust etc, with a lot of bumps and steep climbs.

Thanks to Garijeva Garaža for the photos 🙂

Picture 1

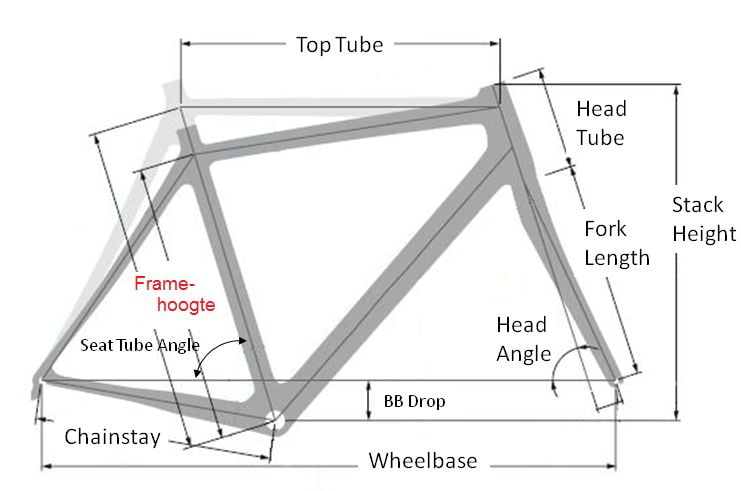

How do MTBs differ from the other bicycles? Generally:

- Frames are designed to accommodate very wide, knobby tyres, for better grip in the mud, and more comfort on bumpy terrain.

- They have low gearing (gear-ratios), so a rider can remain seated even on steep climbs, because riding out of the saddle (“standing up”) unloads the rear wheel, causing it to slip in the mud.

- An MTB is heavier than a road bike of the same class, but it’s sturdier, to more easily take bumps and other off-road riding shocks.

- Since (more than) a few years ago, most MTBs come with suspension (at least in the front – suspension forks), and disc brakes (as opposed to rim brakes).

3. Do I really need an MTB?

I think this is important to stress – don’t fall for the marketing brainwashing:

You can ride the mountain paths even on a bicycle that isn’t an MTB – I’ve been doing that for decades.

Picture 2

Today it is very difficult to find an MTB without any suspension (at least the front one) and disc brakes. Marketing is very powerful, and most people today are convinced that a MTB must have all that. If I hadn’t ridden bikes without suspension and disc brakes for over 30 years, I too probably wouldn’t have believed that. When I say that I rode all over the local mountain with V-brakes, or callipers, and with a rigid fork, people either don’t believe it, or say that I wasn’t riding hard, or long enough. OK, I’m no downhill competitor, nor a “very serious cyclist,” but I think that 100 kilometres in a day on mountain roads is a decent ride.

Of course, mountain bikes make off-road riding easier, and more comfortable, but they are not necessary in order to enjoy the mountain paths.

Suspension and disc brakes are useful, but they also have some downsides. The main downsides are greater weight and more complicated and more expensive maintenance. If you’d like to know more, take a look at these two articles:

Another thing: how many miles is your local mountain away (if you are cycling to reach the mountain)? MTB does handle better off-road, but it’s far from the best choice for the pavement, even the poor quality pavement. See on what kind of roads you really spend the most time on, then weigh all the pros and cons.

Of course, in this article I’m explaining the MTBs that are sold in the market today – they do have cons, but they also have pros.

4. Modern patents (that aren’t always beneficial)

In the article about buying a road bicycle, I devoted the entire 2nd chapter to the modern cycling industry patents that can bring more harm than good. You can read it if you like – 99% of that relates to MTBs as well. Here, I’ll just “hit the high points,” as the Americans say. Let’s roll:

4.1. Disc brakes

If you are buying a mountain bike today, you will hardly find a model without the disc brakes – except on the really low-end bikes. There are two basic disc brake types: mechanical, and hydraulic disc brakes. They are easily distinguished, because mechanical disc brakes have a visible cable, while hydraulic brakes have housing routed all the way (there’s no cable).

Look at the picture 3 below and note the mechanical brake housing stop (1), and visible brake cable (2), then compare it with the hydraulic brake’s full length brake hose (3):

Picture 3

What does this mean for you, on the road? Mechanical VS Hydraulic disc brakes:

- Mechanical brakes are a bit simpler and cheaper to buy and maintain.

- Hydraulic brakes offer slightly better brake-force modulation and require less brake lever pressure for the same amount of braking force (helpful for those with weak hands).

- Hydraulic brakes will self-adjust as the brake pads wear. Mechanical ones need to be manually adjusted as the pads wear – similar to rim brakes.

- Max braking (stopping) power is good for both mechanical, and hydraulic disc brakes. Tyre’s grip on the surface is the bottleneck – not the braking power. But good hydraulic brakes give that max braking power with less pressure on the brake lever, and they provide more even, more gradual brake force modulation.

Decent quality mechanical disc brakes, like Avid BB7 (Amazon affiliate link), are to be respected! They brake better than hydraulic brakes of lower class (cheaper, “low-end” models).

Of course, high-quality hydraulic brakes perform better even than high-quality mechanical brakes.

On the other hand, poor quality disc brakes perform worse than good quality rim brakes. So don’t think that any kind of disc brake must necessarily be good.

Downsides of any disc brakes are: they are heavier, more expensive to buy and more complicated to service, compared to rim brakes.

Are they necessary for riding off-road? Apart from riding in deep mud, I’d say they aren’t. But I must repeat: you won’t find a new MTB with good quality compontents, that doesn’t come with disc brakes.

I should also discuss the system for mounting brake discs onto the hubs. There are two standards:

- 6-bolt mounting system.

- Centerlock.

Centerlock is superior in every way and I don’t understand why the 6-bolt system is still being made and sold. I showed and explained the differences in this video:

Miloš:

I think that the 6-bolt system is better because it holds the disc at 6 different points.

Also, in case something gets lost or damaged, it’s usually easier to source spare bolts, than a spare centerlock lockring.

4.2. Suspension (shock absorbers)

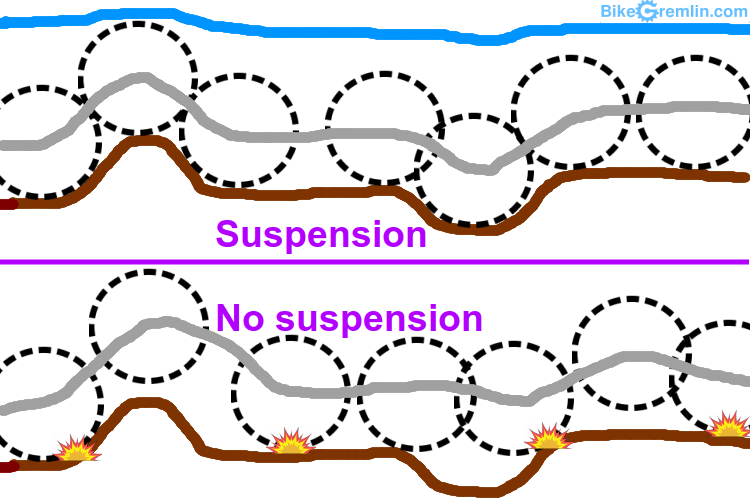

A shock absorber allows a wheel to move up-down, independently of the frame. This helps increase comfort, and improve tyre traction. Instead of a wheel bouncing off into the air when it hits a bump, the shock absorber will allow it to move upwards, following the bump’s curve. Likewise, when there’s a depression in the ground, the shock absorber will push the wheel down, so it follows the depression’s curves, instead of staying afloat in mid-air – and then hitting the ground with greater force a split-second later.

Yes, I draw like a 3-year old. 🙂 Picture 4 shows the path of a wheel with suspension (top), and without suspension (bottom):

Picture 4

The blue line shows the handlebar’s path (how little of the road shocks are transferred to the rider) – when shock absorbers are of high quality and properly tuned. If there are no shock absorbers, handlebars and saddle are moving as much as the wheels – if wheels are bouncing, so are they. You can use your bent knees and arms to help make yourself more comfortable, but even that doesn’t help the wheel stay planted and keep traction – it will still bounce a lot more.

Downsides of shock absorbers are high price, greater weight, and more complicated maintenance (after every 50 hours of riding if you are hard-core, or once a year if you mainly stay on the roads and beaten paths – with fewer bumps and jumps). They also reduce the amount of adrenaline you get when going down-hill – but some might find this to be an advantage. 🙂

4.2.1. Types of suspension

Today you will hardly find an MTB without any suspension. You generally get to choose between:

- “Hardtail” – MTBs with front suspension only (suspension fork).

- “Full-sus” – MTBs with both the front and the rear suspension.

Picture 5

Front suspension makes the ride noticeably more comfortable, and improves steering (keeping the bike going where you want it to, even on bumpy terrain).

Adding a rear suspension further improves comfort, impoves rear wheel’s traction (the drive wheel), and steering, especially when you are bombing down-hill over bumps.

Because of the high price, more weight, and the added frame construction complexity that rear suspension introduces, it is put only on MTBs intended for extreme off-road riding… well, and on very cheap under 400 $ MTBs that are good for nothing and best avoided.

Picture 6

There are many other suspension properties, besides the most basic division to front, and rear, like spring progressiveness etc, but that is beyond the scope of this MTB buying guide. However, I’ll explain one property, most widely used for the front suspension (forks): travel length, or just “travel”.

Travel is how far a suspension fork lowers can move up-down when soaking up the bumps. It is expressed in millimetres and usually ranges from 50 to 200 mm, depending on the suspension model and intended use.

Lowers (black) slide up-down over Stanchions (golden)

Picture 7

Note: bicycle frames are designed for a certain, given amount of fork travel. The acceptable tollerances are within the 20 mm range. If you put a fork that has a lot shorter, or a lot longer travel, bike’s handling could become bad, and the frame could get damaged (cracked).

4.2.2. Suspension quality

A good shock absorber must slow a wheel’s movement in both directions – up, and down. Unlike a simple bungee spring, it shouldn’t let the wheel bounce back without any damping. High-end shock absorbers usually have the following settings:

- Lockout – making the shock absorber effectively act as a rigid rod. Locking out the suspension makes riding up hills a lot easier. Some shocks have a remote lockout, where a cable and housing are connecting the shock absorber to a lever on the handlebars, allowing the rider to lock/unlock the shock while they are riding.

- Spring preload – how hard are the springs, how easily a shock absorber will compress.

- Compression damping – how much does the shock absorber slow down the wheel’s upwards travel – i.e. slowing down of the shock absorber’s compression speed.

- Rebound damping – how much will the shock absorber slow down the spring-back phase, when the wheel moves downwards after the shock absorber was compressed.

- Really high-end shocks have additional rebound, and/or damping adjustments for short, and for longer shock absorber travel. These are called “low-speed, (LSC)” and “high-speed (HSC)” compression settings, or LSR, and HSR for rebound settings. Explaining those is beyond the scope of this article.

How can you recognize a high quality shock abosrber (either rear, or the front)? Generally:

- The lockout option can come in handy – mid-range and low-mid-range shocks usually have that option, while low-end and some high-end models don’t.

- It should also have the rebound damping adjustment.

- Spring preload adjustment goes without saying.

- Low and middle-price range forks with air “springs” are noticeably better. Coil spring forks that aren’t high-class (around a 1,000 $ price range) are better avoided.

I consider these a bare minimum for considering a shock absorber to be remotely decent.

Roughly speaking, very oversimplified: look for MTBs with front suspension only, that satisfies the criteria listed above (marked blue).

Shock prices vary drastically depending on the intended use (type of riding and terrain), but I don’t think I’m lying if I say that decent new shocks start from 200 $ (goes both for the front, and the rear ones) – to over 1,000 $ for the high-end models.

Shocks that cost under 100 $ are so bad that I think it’s better to ride a fully rigid bike, than with such poor-quality suspension.

Today, you won’t find a new MTB with good-quality components, that doesn’t come with at least the front suspension.

4.3. Tubeless tyres

Tyres without tubes. Until relatively recently, bicycles had tubes to hold the air, and tyres to provide the grip. Now, like with cars and most motorcycles, bicycles are going tubeless more and more.

On the outside, tubeless tyres look almost exactly like the “ordinary” tyres, but they are capable of holding the air pressure without the aid of a tube (though, they do need the aid of the sealant fluid).

In the article about road bike buying, I wrote in more detail about the pros and cons of bicycle tubeless tyres. Briefly:

They are more of a hassle, but they do allow you to ride with lower tyre pressure, without risking any pinch (snakebite) flats. Lower pressure can improve tyre traction in the mud, sand, snow etc. But, tubeless tyres require more hassle with regular sealant fluid replacement, and they are more difficult to mount, or patch if they get punctured with a hole too large for the sealant to “self-patch” them. For more details see:

4.4. Dropper seatposts

In the article about the pros and cons of bicycle suspension, I wrote about dropper seatposts, and suspension seatposts (the two aren’t the same thing).

Dropper seatpost can retract, and extend back using a switch of a lever – often remotely, with the control lever mounted on the handlebars.

Picture 8

How can this be useful? If you set your saddle to the optimal height for pedalling, you won’t be able to bend your knees much, before your back hits the saddle. On large bumps, and landing after jumps, it helps if you can bend more at the knees to cushion the shocks.

The dropper seatpost can be retracted with a flick of a switch, so it sits “too low” for normal pedalling, but gives you room for more movement when you need it – and you can always switch it back for comfortable pedalling. It’s faster and more convenient than stopping and manually adjusting your saddle height as the trail changes from relatively flat, to huge bumps and jumps.

Dropper seatpost downsides? More weight, more complexity that requires maintenance (regular service), and those with internally routed control cable… well, see what I think of the internally routed cables and housing.

Miloš:

Dropper seatposts are awesome! 🙂

4.5. Other novelties

The above noted patents are more tightly related to MTBs. There are some other patents, used throughout the cycling industry, that can make maintenance more complicated and more expensive – though some of them also offer great advantages.

I wrote about them in the article about road bicycle buying, so here I’ll put links to those chapters, with brief comments:

- Internally routed cables and housing – impractical, but unavoidable on modern frames.

- Press-fit bottom brackets – they can cause creaking problems with some frames, in which case the proper patch is a 200 $ Hambini bottom bracket insert (more details are in the linked chapter).

- Carbon-fiber frames – pros and cons (risks).

- Thru-axles vs quick release.

5. MTB types

There are many types of mountain bike riding and MTB types designed for each. I’ll note a few, let’s call them “basics.”

5.1. XC – Cross Country

This type of MTBs could be regarded as “forest Ferrari.” 🙂

They are designed to be as light and as fast as possible when riding uphill, or on relatively horizontal mountain paths. They often have only front suspension (“hard-tail“).

They make up most of the bikes we see in the streets, and forests. They aren’t the champions of rough-terrain downhill riding, but are far from a bad choice for enjoying such riding as well.

XC bikes come in two flavours: XC race, and XC trail. Comparing the two, XC race are generally lighter, and with a geometry that puts the rider’s weight more towards the front – to allow for the fastest possible riding on the straights, and taking sharp turns. XC trail bikes can be regarded as a bit sturdier, heavier, and with a more relaxed riding position.

Differences between the XC race, and XC trail are not very big:

Picture 9

Picture 10

For beginners, if you don’t know exactly what you’re looking for, XC trail MTB with front suspension only (hard-tail) is a great choice to start with.

They come with a suspension fork travel of 80 to 120 mm, reducing the impact of (smaller) bumps and holes, without making the bike too heavy, or too… how should I put it… wobbly, non-rigid.

Miloš:

This kind of bicycle is the most universal. With slicker tyres, it instantly turns into a touring, backpacking, or even a commuting bicycle – while still being good for enjoying the rides in the forest.

5.2. Enduro, All-Mountain

This is a “Jeep” of MTBs.

They usually come as full-sus, with a 140 to 160 mm suspension (fork) travel.

Slower up-hill compared to the XC bikes, but faster over more rough terrain, technically challenging trails, and fast descends along very bumpy paths.

Picture 11

5.3. DH – Downhill

The cycling version of bob-sleigh (YouTube link). 🙂 Miloš says that “monster truck” is a better comparison. 🙂

DH bikes usually get transported by a car to a top of a hill, so the rider can bomb down with great speed, over very bumpy terrain. Which requires good reflexes, skill, and a good level of fitness, because the suspension isn’t all-powerful.

Talking about suspension – these are always full-sus bikes, with a fork travel of 170 to over 200 mm.

They are very strong, with high-quality suspension. The good ones cost over 3,000 $.

DH MTBs are slow, and a poor choice for riding up hills, or even on flats. They are designed for downhill. Period.

Picture 12

5.4. Freeride

A bit more difficult to define, with several sub-types. Somewhere in between the XC and DH MTBs… Mad Max film vehicles come to mind, don’t know why. 🙂

This kind of riding has it all: from fast descends, over jumps and stunts, to fast riding on flats and even uphill. It’s called “Freeride” for a reason! 🙂

Freeride bikes are usually full-suspension, with a fork travel of 160 to 180 mm – but riders often customize their freeride bikes to suit their own style.

Picture 13

5.5. DJ – Dirt Jump

Running up to a slope made of soil, or other materials, in order to get airborne, and do stunts in flight, hopefully landing on wheels. 🙂

DJ bikes are often with steel frames, very simple, in order to better stand many drops and hard knocks. Smaller size, and no rear suspension, for easier flipping in the air. Sort of a cross between a BMX, and an MTB.

Picture 14

6. Wheel size: 26″, 27.5″ and 29″

Modern MTBs come in three different rim sizes. I’ll list the rim diameters in millimetres, followed by the popular marketing name for each standard:

- 559 mm – 26″ (it’s read: “26 inch”).

- 584 mm – 27.5″.

- 622 mm – 29″, or 29er (“twentyniner”).

Yes, these last ones are the same size as your road bicycle wheels, which are then called 28″ !?!

Marketing does wonders! 🙂

Picture 15

In a separate article, I wrote about the pros and cons of each wheel size in great detail:

MTB wheels: 26″ vs 27,5″ vs 29″ 29er

Here I’ll just explain the basics, briefly:

- 26″ wheels are the strongest, the easiest for manoeuvring in tight spots, but they are the slowest-rolling.

- 29″ wheels are the opposite – weakest, but fastest rolling.

- 27.5″ are in between those two when it comes to pros and cons. With the most limited tyre choice in the market (in my experience at least).

I’d recommend an MTB with 29″ wheels for everyone, except riders shorter than 165 cm, who should consider smaller wheel sizes. Smaller wheels, being stronger, also make sense for the really aggressive riding (DH, DJ etc).

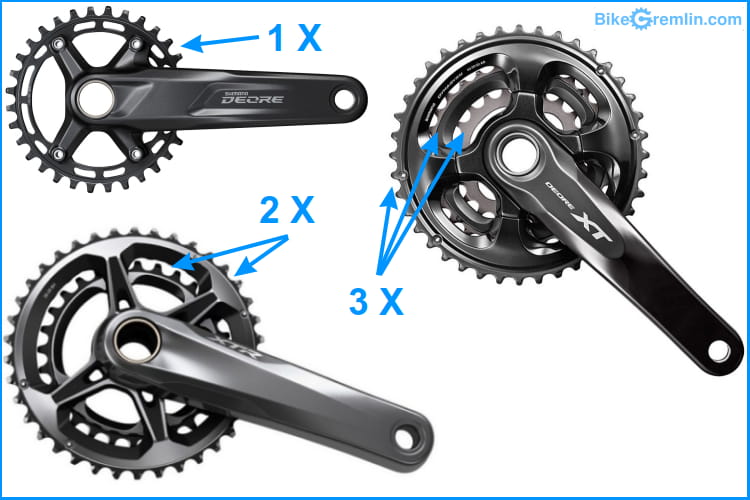

7. Cranks: 1x, 2x, or 3x?

Bicycles with 1X drivetrains (read: “one-by”) are getting more and more popular. Pushing out the older 2X systems, while the 3X systems have long been “relegated” to the lower-end groupsets.

Picture 16

I’ve already explained the pros and cons of 1X systems, compared to 2X, and 3X. Briefly:

- If you are a competitor in great shape, or like following trends – get a 1 X.

- If you want good quality parts (middle, and higher class groupsets) – get a 2 X.

- If you are on a budget and don’t care about the trends, as long as it all works properly – get a 3 X.

8. MTBs for women

If we compare an average woman, to a man of the same height, we will most often see the following differences:

Woman has narrower shoulders, wider hips, longer legs (and shorter torso), smaller hands, and weighs less.

Some manufacturers will just make a smaller sized frame, colour it pink, and be done with their “design” of a woman’s MTB. Others, however, will take all the important differences into consideration – when choosing both the frame tube design (geometry), and handlebar width, saddle shape, suspension firmness etc.

Must women buy women’s MTBs? No. Absolutely not. Bars and saddles can be swapped, and suspension can be tuned. It’s a lot more important to get the appropriate frame size for your height.

9. Handlebar width

I’ll say it right away: handlebars can easily be swapped for wider, or narrower. There are some guidelines, but the optimal handlebar width is very much down to personal preferences.

A good starting point, middle ground, is with arms stretched out at about 45 degree angle, the forearms should be parallel to the bike forward axis. Like in the picture below:

For both good power AND stability.

Picture 17

For those interested in more details, I wrote a whole article about MTB handlebar setup.

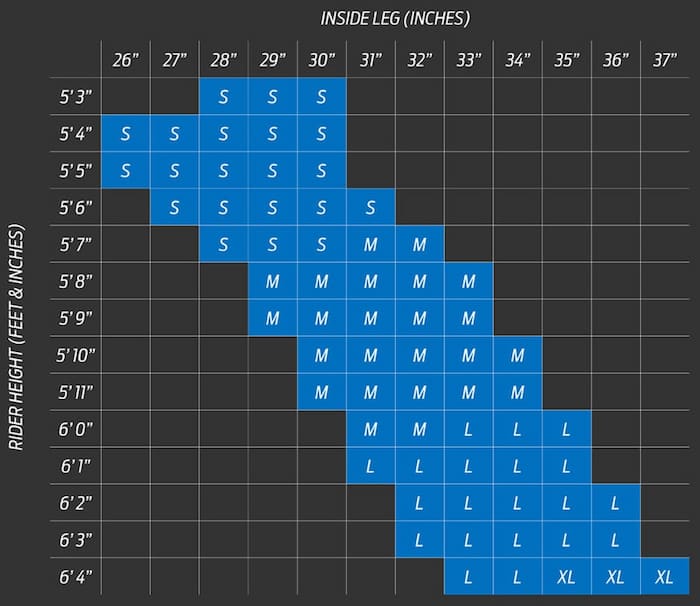

10. IMPORTANT: Frame size

Most things on a bike can be replaced and adjusted, but if you get a frame that is “two sizes” smaller, or larger than you need, you’ve thrown the money away.

High-quality modern MTB frames are usually sold like the T-shirts, in sizes: S, M, L, XL… 🙂

Manufacturers provide a list of rider heights (in cm, or feet & inches) that fit a given frame size. For example, here’s the sizing chart for the Giant Fathom 29 1 – XC MTB:

Picture 18

If you need it: on-line feet & inch to cm converter (give me the metric system, or give me death! 🙂 ).

As you can see from the pic, a 5’7″ cyclist, with a 30″ inside leg, can choose either S, or M sized frame. The choice boils down to personal preference (some people prefer smaller frames). But such a rider should not choose an L sized frame – it will be too big, and won’t fit.

Miloš:

If you ride technically challenging trails, and your height fits two different sizes by the manufacturer’s charts, it is better to go with the smaller of the two.

For longer distances and more “open” trails, it’s better to go with the larger of the two (again, if more than one size fits your height, by the manufacturer’s sizing charts).

Some sellers only state the seat tube length – in inches, or centimetres. In the article on how to choose a correct bicycle frame size, I’ve explained why such numbers are useless without the manufacturer’s sizing charts. Here, I’ll just put a picture explaining the problem:

They are effectively the same size!

Fitting the riders of the same heights.

Picture 19

So, if someone tells you: “you should get an 18 inch frame,” know that the person may not know what they are talking about.

Such statements only make sense when they are referring to a particular frame (bicycle) model. For example:

“For the Giant XTC ADVANCED SL 29, you need a 17 inch seat tube length” (which is the M size frame for that particular model).

11. Groupsets (equipment classes)

Many people get “hung up” on dereilleur and groupset classes: “is it XT, is it Deore,” etc. It doesn’t really matter.

Good quality frame, wheels, and good suspension are of crucial importance. Shifters, derailleurs, and brakes are not too expensive to replace if you’re not happy with them.

Besides, because everyone is looking at the derailleurs, I’m yet to see a bicycle manufacturer who puts a good quality (and expensive) suspension on a bike, and then fits a poor quality rear derailleur.

Briefly: Shimano Deore, or SRAM X5 – or any higher class, are very good. I’d even say that Shimano Acera is perfectly fine. For more details, see: Bicycle equipment (“groupset”) classes.

Again: manufacturers cut costs on the most expensive stuff that no one looks at – frames, suspension and wheels. Derailleurs are usually the brightest spot on the bicycle, compared to the other components and the bike’s price range.

12. The best MTB in the world!

There is no “best MTB.” There’s only an optimal choice for you, based on your preferences, riding style, and budget.

If you are just entering the world of (mountain) biking, I recommend you start with a basic, XC trail MTB type: with an aluminium frame, decent quality brakes, derailleurs, shifters, and with front suspension only (hard-tail). Definitely don’t get hung up on the bike having”at least Shimano XT,” or “SRAM GX Eagle” groupset etc. Why?

A vast majority of people don’t know exactly what kind of riding or what kind of bicycle they will love the most. For all of us, it takes a bit of trial and error to figure that out.

I know – you don’t believe me. You’ve asked around, read a lot, perhaps even tried some MTBs and you are convinced that you know exactly what kind of riding you’ll be doing 99.9% of the time. 🙂 In my experience, three out of four people don’t get this right:

- You can’t really know if you like riding through mud, until you do at least 10 good rides in the mud.

- In order to see if you like bombing down hills, you need to learn the technique, overcome fears, know how to do it – only then can you really tell if you like that sort of adrenaline, or prefer pavement or more beaten paths.

That’s why it’s safer for your first MTB to be NOT too expensive.

But! It is also bad if your first MTB is of poor quality, too cheap. Riding a bike that’s always poorly shifting, poorly braking and handling, will get you to feel sick of riding, and you won’t enjoy it – not realising what you’re missing.

Decent quality hardtail MTBs start around 1,000 $. Aluminium frame, hard-tail, with a basic decent quality suspension fork, good quality brakes and derailleurs. Good quality suspension isn’t cheap, and if you are looking at new MTBs in the under 600 $ range, it’s best if they are 100% rigid (if anyone sells these anymore) – or you’ll get some very poor quality suspension, and most probably, brakes and other components (like a freewheel rear hub, instead of a freehub).

What about used (2nd hand) MTBs? You basically pay half the price of the new one, but you need to access their condition before buying in order to avoid any expensive repairs. See: Buying (checking) a used bicycle.

13. Under 800 $ MTB

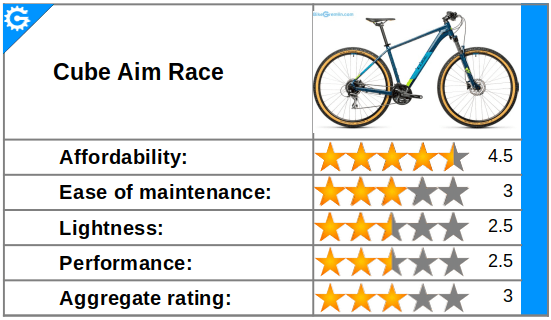

In “the cheapest that’s any good” class, I’d single out Cube Aim Race.

Picture 20

- Price: around 800 $.

If this is too much for your budget, see my article: New MTB for under 400 $ (buying cheap). - This bike comes with a quite decent aluminium frame. I think that’s important – everything else can be more easily replaced, “upgraded.”

- XS, and S sized bikes come with 27.5″ wheels, while M and larger ones come with 29″ wheel size.

- 3 front chainrings, with 8 in the rear, give a huge gearing range (for the steep climbs, and fast descends), at an affordable price. Simple, sturdy, durable.

- The rear derailleur is Shimano Acera – and in my experience that works quite well.

- Hydraulic Shimano Altus brakes work surprisingly well considering their price (and that groupset’s class in Shimano’s hierarchy).

- The suspension fork is basic, but at least has a lockout. SR Suntour XCM (similar to XCR, and XCT). Designed for the beaten off-road paths (“gravel”), not for any really rough terrain.

Some models in this price range come with RockShox Judy Coil fork – which is very similar and I wouldn’t call it better – another very basic, low-quality shock. - Internally routed rear brake and derailleur housing will provide you with more “fun” when it’s time to replace them, but that’s inevitable on 99.9% of today’s bikes.

My comment:

With this bike you can go to the forrest and enjoy the ride. If you get hooked, you are likely to be looking for improved front suspension, perhaps even better brakes. But it’s not a bad MTB.

Looking at the offers and the prices, it seems that a vast majority of bikes below this price are so poor quality that you are more likely to be fed up with cycling. For a lower budget, it makes more sense to look for a bike without any suspension, or disc brakes – even for forest riding, even if such bikes aren’t marketed as “mountain bicycles.”

14. Around 1,300 $ MTB

I have deliberately “skipped” any models with 1X drivetrains (only one front chainring). I think such systems are better suited for very fit competitors who choose the chainring and cassette configuration to fit each track they are racing on. Bikes with two front chainrings are, in my opinion, better suited for recreational riding: they offer a wide gearing range, at a more affordable price.

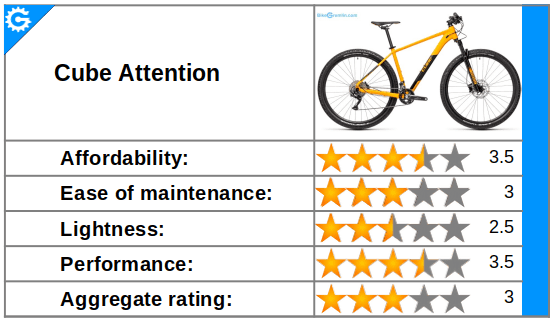

My pick is Cube Attention.

Picture 21

- Price: around 1,300 $.

- This bike comes with a good quality aluminium frame.

- XS, and S sized bikes come with 27.5″ wheels, while M and larger ones come with 29″ wheel size.

- 2 front chainrings, with 10 in the rear, provide a wide gearing range, with fast shifting.

- The rear derailleur is Shimano Deore – very good.

- Hydraulic Shimano Altus brakes work surprisingly well considering their price, but I would like to see something better at this price range.

- The suspension fork is decent, with a 100 mm travel.

- Internally routed rear brake and derailleur housing are unavoidable today… unfortunately.

My comment:

Cube Attention is a pretty well rounded bike. My heart says “ask the dealer to throw in Shimano Deore brakes for around 100 bucks more,” but my brain says that Shimano Altus hydraulics have been improved in 2020 (if memory serves me) and aren’t that bad at all.

This bike is a step up from the above-discussed Cube Aim Race in every way. There are thousands of models in the price range between the two, but most are lacking either in suspension, or gearing. So you’d be paying a bit more compared to the Cube Aim Race, but won’t get a noticeably better experience.

For a real step-up from the sub-800 $ MTBs, you must look in the 1,300 $ price range (definitely over 1,000 $). You don’t have to go with Cube Attention, there are other bikes in this price range, but do look for a decent quality air suspension fork, and a good quality drivetrain and brakes.

15. Full-suspension MTB

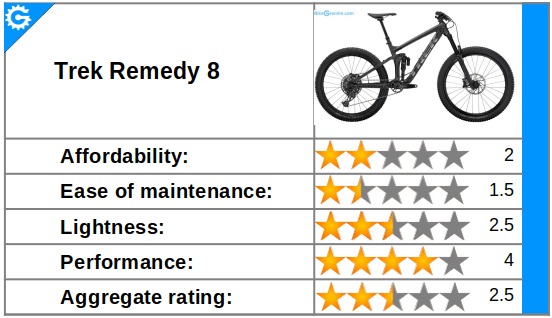

An MTB with both the front and the rear suspension can’t be cheap in order to be any good. At around 4,000 $ comes Trek Remedy 8 (link to the Trek’s website).

Picture 22

- Price: around 4,100 $.

- Good quality aluminium frame, with a curved top tube on smaller sized models, so the rider can more easily stand over the bike.

- Press-fit bottom bracket – with all the pros and cons of this design.

- 27.5″ wheels – not a huge range of slick tyres in this size, but this bike is intended for mud, rocks, and other off-road terrains, so you’ll probably be going with knobby tyres anyway.

It comes with tubeless tyres – with all their pros and cons. - SRAM GX Eagle 1×12 drivetrain – a solid choice for a drivetrain with only one front chainring.

- The rear derailleur is also SRAM GX Eagle – very good.

- SRAM Code R hydraulic brakes with 4 pistons – a solid choice.

- RockShox Lyrik Select+ front suspension, with 160 mm travel – good quality.

- RockShox Super Deluxe Select+ rear suspension – also good quality.

Both suspensions come with DebonAir™ spring, which, if off-road riders more experienced and advanced than I am are to be trusted, offers coil-spring-like function, with no binding at the start of the travel, which is a problem with many air-suspension shock absorbers. - This is a high-quality bicycle, but it’s not a competitive racer class. There should be a special circle in Hell for the people who design internally routed housing on bikes for recreational riding.

My comment:

Pretty high-quality, well-rounded all-mountain MTB. Thanks to the good suspension choice, it is good going up-hills, and capable of rushing downhill (of course, I must note: this isn’t a hard-core DH bike). For bikes that aren’t a top-competitor class, 2×10 drivetrains make more sense than 1×12. However, 1×12 sells better, plus it makes the frame’s rear suspension linkage design simpler. For the manufacturers – that’s a win-win.

A carbon-fiber frame would have made the bike a bit lighter, but would also have raised the cost for at least another 600 $.

16. DH MTB

Bikes for fast descending over rough terrain. Good shock absorbers and high quality brakes are very important here. These things are expensive – so there’s not much room for the bike manufacturers to keep the prices low – if you want a good quality, safe bicycle for bombing down hills.

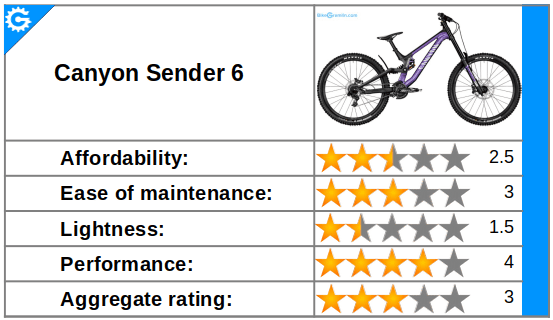

My pick here is Canyon Sender 6 (link to the Canyon’s website).

Picture 23

- Price: around 3,400 $.

- Good quality aluminium frame, with a BSA (threaded) bottom bracket.

- 27.5″ wheels, with good quality rims and hubs – but only 28 spokes.

Why put only 28 spokes on wheels for bombing downhills?! - SRAM GX DH 1×7 drivetrain – simple, robust, without a huge gear ratio range – since this is a bike for going down hills.

- The cranks are Truvativ Descendant DH, with a 34 toothed chainring.

- SRAM Code R hydraulic brakes with 4 pistons – a solid choice.

- Front suspension is Marzocchi Bomber 58 – a no-nonsense DH suspension, at a reasonable price, with 200 mm travel.

- The rear suspension is also good, Marzocchi Bomber CR, with 200 mm travel.

- Cables and housings are routed under the down-tube, behind a plastic cover – a brilliant solution.

My comment:

First a standing ovation for the externally routed cables – a brilliant solution that deserves a picture: 🙂

Picture 24

This design prevents any annoying rattling of housing inside the tubes, plus it makes housing inspection and replacement very fast, simple and easy. With a plastic cover to protect them from any damage. Beautiful.

This is a solid DH MTB. The most important stuff, suspension and brakes, are good enough.

If I had to complain, I’d take it out on the wheels. Only 28 spokes, and a 6-bolt, instead of a centerlock disc mounting system. I’d rather see 36 spokes and centerlock disc mounts.

At 17+ kg, it’s not very light, but for a few kg less the price would need to go up by around 1,000 $.

The price is very reasonable for a decent DH MTB.

17. Conclusion

I wish I had a dollar each time a cyclist was shocked by the price of a fork service (overhaul), or the price of a new, high-quality suspension fork.

That’s why, in this “complete MTB buying guide,” I’ve tried to explain what is important, what to pay attention to, along with all the pros and cons of many modern cycling industry patents (disc brakes, suspension etc.). So you don’t get to the: “OH, I had no idea that costs so much!?”

If you are on a tight budget, don’t go for a bike with all the bells and whisltes – it will either be of poor quality, or cost a lot to keep running (one not excluding the other).

Miloš:

A lot of high-end bicycles from abroad are being sold locally, as 2nd hand, for 600 to 1.000 $. The problem is that high-end bicycles have a lot of expensive equipment, that costs a lot when it is time to replace. For example, a new 1×12 cassette can cost around 200 $. Chains are also expensive. High-end suspension can make it difficult to source spare parts (in Novi Sad) and service labour costs over 100 $.

18. Appendix – buy a new or used MTB?

Many people have this dilemma and have asked me this, so I wrote a separate article about whether it’s better to buy a new, or a used bicycle (in general, regardless of the bicycle’s type).

Here, I made a second-hand bicycle-buying tutorial (with a video).

This is a list of my bicycle-buying guides, sorted by bicycle type:

- Road bicycle buying guide

- Mountain bicycle (MTB) buying guide

- Trekking bicycle buying guide

- City bicycle buying guide

- Commuting bicycle buying guide

- BONUS: Is it better to buy a new or a used bicycle?

- Kids’ bicycles – how to pick the right size?

Last updated:

Originally published: