In this article, I’m talking about using very old, or vintage, frames for assembling bicycles that are relatively cheap to put together, and fairly simple and cheap to maintain (service).

At the end of this article, there’s a video where I demonstrate most things mentioned here.

1. Why would anyone use a vintage frame?

I thought you’d never ask! 🙂

There are several reasons. Let’s dive in:

- Huge supply, often very cheaply, or even for free (best things in life are free).

- They are often durable and reliable.

- They don’t fail suddenly and completely, without any prior warning, like the modern carbon-fiber frames and forks.

- Putting an old frame back in service instead of building a new one is environmentally friendly.

- They’re damn cool looking! 🙂

It’s a good structure for building a cheap, reliable bicycle that’s easy to maintain – so you don’t have to wait for weeks during the seasonal bicycle repair shop overload.

What about the potential complications, gotchas, and caveats? Read on.

2. Potential deal breakers

When considering a vintage bicycle restoration, the fist thing I check is whether everything can be removed from the frame.

To be more precise, the sentence above could be phrased like: “I check if everything can be removed with an acceptable amount of time and effort.” Sure – with some chemistry and top-class tools anything can be done, but I don’t always feel like spending tens of hours just to make a frame functional. For the things that have a sentimental value, not measured in time and money, I’ll dedicate separate articles.

Here’s a short list of the potential party-stoppers:

- Cracked frame, or dented tubes. Any of those generally leads to a total failure sooner, or later (why are dented bicycle frame tubes weak).

- The seat post can get stuck. This means you won’t be able to adjust the saddle height, or change the seat post in case it gets damaged (the saddle mounting mechanism is what sometimes gets damaged).

- Stuck bottom bracket cups, or BB cartridge. They get worn over time, develop play, and if they can’t be removed and replaced, it makes the frame have a very limited “best-before” date.

- The bottom bracket shell standard is not British, or at least Italian (see threaded bottom bracket standards).

If all that is good, you’re in luck. Just – whatever you mount on the frame, make sure to use an appropriate mounting (anti-seize) paste, so nothing gets stuck so it can’t be removed and replaced later on.

Now let’s see about the important things to consider:

3. Bottom bracket

Old frames come with all sorts of bottom bracket standards. In a separate article, I explained and provided the dimensions for various threaded bottom bracket standards. The most commonly seen are British (“BSA”), and Italian threaded standards – but it’s not unlikely you will come across something more “exotic.”

Today, spare bottom brackets can easily be found for the British (BSA) standard, and with a bit more hassle you could also source the Italian standard ones. The rest are a lot more difficult to come by, so I would avoid frames with “exotic” bottom bracket standards.

How can you determine which standard is on the frame? It’s best to remove the bottom bracket cups (or cartridge), take a look and measure.

If there aren’t any threads, it’s an obsolete press-fit standard. To fix it you need a donor BB, cut and machined out of a frame with a British standard threaded bottom bracket. Then whacked into the frame, after a few hours in the freezer. That’s a bit of a hassle.

If it has threads, measure them. The left cup is always unscrewed anti-clockwise (it has the standard, right-handed thread). Once you’ve removed it, you can measure the diameter, either on the cup, or on the frame:

Picture 1

If the diameter is over 35 mm, then it’s an Italian standard BB, so the right hand side cup is unscrewed counter-clockwise (i.e. to the left).

If the diameter is under 35 mm, as shown in picture 1, then it could be British standard. In that case, the right-hand side cup is unscrewed clockwise (it has a left-handed thread). However, if you have really bad luck, the frame might have a French standard bottom bracket, in which case turning the right cup clockwise will only further tighten it (as is the case with the frame in picture 1)! That’s tricky because the diameter is the same, and the thread pitch is very similar.

If you are trying to turn it clockwise and it won’t bulge: are you turning it the wrong way, or just dealing with a stuck (seized) cup? We don’t know. Try to find more info on the frame, or see if there’s some description printed (or stamped) on the cups.

You can also measure the frame’s bottom bracket shell width. Italian standard ones are 70 mm wide. The others are 68 mm wide – with an exception that British standard ones can also be 73 mm wide, or wider (in addition to the common 68 mm). So if a BB shell is wider than 68 mm, it’s definitely not a French standard one.

Picture 2

Once you’ve removed the cups and confirmed the frame’s BB standard, you can find replacement British, and Italian standard cups for both square taper, and the modern, Hollowtech II cranks:

Picture 3

4. The distance between the rear wheel dropouts

Modern rear hubs are readily available in 130 mm OLD (“width”) spacing for road, and 135 mm for MTB hubs (bicycle rear hub OLD width standards).

Vintage frame rear wheel dropout spacing is often 126 mm, or less.

The acceptable difference between dropout width and hub’s OLD is 2.5 mm. Anything more than that leads to frame damage – even if a wheel can be squeezed in. I repeat: dropouts that are up to 2.5 mm wider, or narrower than the hub’s OLD are perfectly fine, but anything more than that is risky.

4.1. Cold-setting the dropout width

Fortunately, steel frame dropouts can be widened (or narrowed down for that matter) with no special tools required.

Note: aluminium or carbon frames will be damaged if you try to widen their dropouts! Titanium? I expect it to be a lot more hassle (for reasons beyond this article’s scope), but theoretically possible (I’ve never tried it).

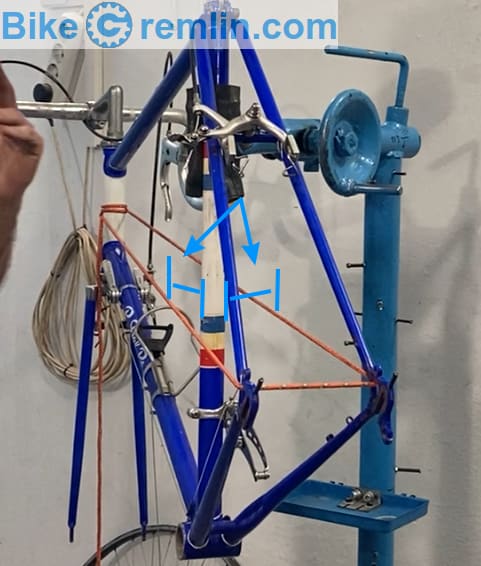

This can be done using some improvised tools: a 30+ cm long threaded rod, 10 mm wide, some nuts, and washers:

Picture 4

Thread 2, or 3 nuts on one end, and tighten them against each other (like lock-nuts) – so you can hold that side more easily in place. Then just move one nut and washer to that side, to lean on the frame, and use a wrench to turn the nut on the opposite side, spreading the frame.

Lubricate the threads, especially if the frame has very thick and strong tubes.

Because steel is flexible, you’ll have to turn that nut until the frame is spread to about 150 mm, or more – so that, when you unscrew the nut, and the frame springs back to a certain degree, it ends up at about 130 mm width (if that’s what you’re aiming for). Basically, it’s a bit of a trial and error – you could start with 145 mm, then go with 5 mm increments, checking after each spread, to see at which width the frame springs back.

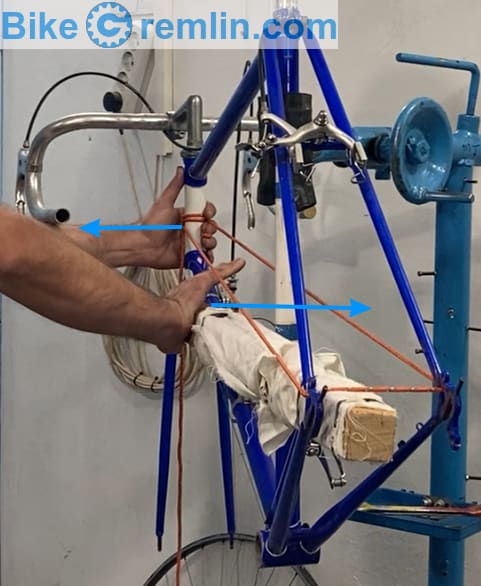

Before doing that, check the frame’s alignment. This can be done by threading a string through the rear dropouts, and over the head tube, then measuring the distance between the string and the seat tube:

Picture 5

If the distance is the same on the right, and the left hand side, then it’s all good. If it isn’t then you need to spread the side that is nearer, to make them even, centered:

Picture 6

All you need is a lever – preferably coated with some cloth, to avoid damaging the frame.

Archimedes

You could use the similar principle to make the frame narrower, if that’s what you’re aiming for:

Picture 7

After decades of consoling myself, attempting this procedure has proven beyond any reasonable doubt that thickness and length do matter, regardless of all the stamina, skill and technique. 🙂

If you spread the rear dropouts to 132.5 mm, you’ll be able to use both road hubs (130 mm wide), and MTB hubs (135 mm wide).

After spreading the frame, the last step is making sure the dropouts are paralle to each other, and aligning them if needed:

Picture 8

Depending on the exact point at which you are measuring the dropout width, aligning the dropouts after having spread them could reduce the spacing by a few mm. Double check.

Here’s what Unior’s dropout alignment tools look like (Amazon affiliate link):

(Amazon affiliate link)

Picture 9

5. Threaded forks

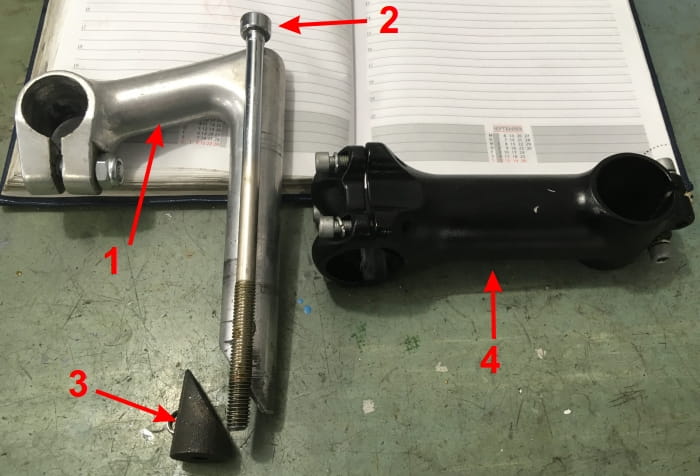

A great majority of vintage frames (as well as the new frames on budget bicycles) have a threaded fork, with a quill stem.

In a separate article I showed and explained threaded and threadless forks.

Briefly: setting the optimal headset bearings preload (so there is no play, but it’s not overtightened) is a lot more difficult with threaded forks. They are held in place by a nut, which is held in place with a lock-nut. 🙂 As you start tightening the locknut, holding the nut in place, the nut turns a bit, so you need to make several trial-and-error attempts to get it just right. Can be a bit frustrating.

Source: bicycletutor.com

Picture 10

With threaded forks this is a lot simpler:

By tightening the top-cap bolt (1), preload is increased (2)

After it’s set, tighten the sem in place using its pinch-bolts (3)

Picture 11

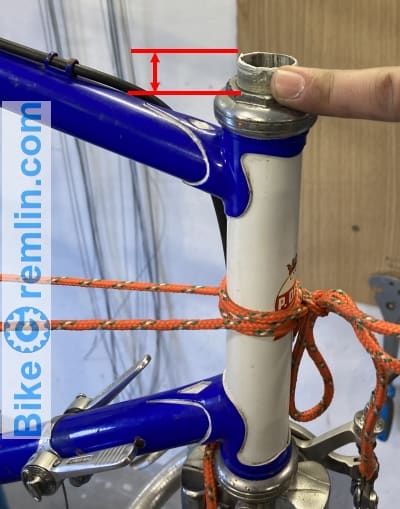

Can a threadless fork be mounted on a vintage frame?

These frames usually have a head-tube for forks with a 1″ steerer tube diameter. Matching headset cups aren’t wide-spread, but can be sourced. But 1″ threadless forks are difficult to find.

What can be done is finding a threaded steel fork, with a steerer tube long enough for the threadless stem to be mounted on it. It’s worked for me – steel steerer tubes are strong enough to survive such improvisation, in spite of having threads cut into them (which does weaken them to a degree). Just make sure to use an aluminium stem – steel ones are too hard, while carbon fiber ones could get damaged when tightened on a threaded steerer tube.

Picture 12

Good length, but the steering tube is too thick (1 1/8″, i.e. 28.6 mm):

Picture 13

Is this really necessary? Why should I bother with this? I’m explaining that in the next chapter:

5.1. Front wheel dropout width

Bicycles from the past 30 years rarely have this problem, but with bicycles that are older than that, you may come across it. Modern front hubs are designed for 100 mm wide dropouts (some modern “thru-axle” hubs are designed for 110 mm). However, on bicycles that are 50+ years old, you can often come across 90 mm wide front wheel dropouts.

Some modern hubs allow you to use thinner (narrower) locknuts in order to reduce the total width. This is a hack, not a design feature, but it can work, depending on how narrow locknuts you have at hand and how the hub was designed (if the original locknuts were wide enough to make a difference of at least 7 mm less).

Another option is to try spreading (cold-setting) the fork legs. Here, the problems can arise:

- If one fork leg goes further to the side than the other, it will negativelly affect steering.

- Likewise, if one fork leg is as much as 1 mm more towards the front, or the rear, it will make the wheel sit at an angle and also negatively affect steering.

It is very tricky to align fork legs using home DIY tools.

Unless saving all the original parts is of great importance, it’s worth giving it a shot and, if the steering is off, consider finding a fork with 100 mm wide dropouts.

Video on fork dropout width:

6. Quill stems

Quill stems are practically a standard on most old, or modern low-end, or “retro – vintage” frames. They are an inherently unsafe patent! I wrote about it in the unsafe and bad cycling industry patents article. Briefly:

Quill stems are held in place via only one bolt, that can break suddenly, without any prior warning. Yet it is highly impractical taking it out for inspection each day. When the bolt breaks, you lose control over the steering – i.e. turning the bars won’t affect the front wheel.

Good quality threadless (ahead) stems don’t have these problems – they are secured via two bolts. It is extremely unlikely for both bolts to fail at the same time.

Picture 14

When I say this, there’s always that one guy who says something like: “I’ve been riding a bike like that for years. Thousands of people ride quill-stem bikes every day.”

That is perfectly true. However, it is also perfectly true that the bolt can snap without any prior warning. I’ve had that happen, and have seen bikes with that problem in my garage over the years.

You must decide whether this is an acceptable risk for you. If it isn’t, you can see some solutions in the previous, 5th chapter of this article.Z

7. Down tube friction shifters

Friction shifters don’t have pre-set clicks, but are just moved until the derailleur moves the chain over to the adjacent chainring, i.e. changes the gear. They are very durable and robust but do require a bit more concentration when shifting.

On retro road-bike frames, they are usually on the down tube:

15

Some people find the down tube shifter position to be impractical, forcing them to take a hand off the bars in order to shift. This can be “fixed” by mounting housing stops instead of the down tube shifters. You can then mount the shifters of choice on the bars, and guide the shifter cable housing to the housing stops on the downtube.

(Amazon affiliate link)

Picture 16

8. Rear derailleur hanger

Some old frames have no rear derailleur hanger, or they do, but it’s damaged beyond straightening and repair.

Picture 17

Picture 18

If you wish to install a more modern direct-mount rear derailleur on a frame without a hanger, you’ll need a rear derailleur hanger adapter:

(Amazon affiliate link)

Picture 19

9. Conclusion – is it worth restoring an old bicycle?

Old frames can be re-used to make great bicycles. Both for commuting, and for recreation. And no, you don’t need a mountain bicycle to go riding in the woods, in spite of what marketing experts are saying.

For the ease of maintenance, it’s simpler if you adjust the frame so you can use the currently available components (rear hubs, bottom brackets etc.). Of course, there’s no reason to throw away any old parts while they are still working. Just make sure, if you are investing some time and money, that you have a platform that can be maintained in the long run (so you don’t have to “retire” the bike once its bottom bracket bearings wear out, for example).

In my opinion and experience, steel frames with British standard bottom bracket threads are a perfect candidate for easy restoration, with minimal modifications.

For bikes with sentimental value, don’t let any of the above-noted problems stop you! As it is nicely shown in the Story of one bicycle, and 40 years.

10. Video demonstration of this story

Last updated:

Originally published:

The existing comments posted under this article (questions and answers) have been moved to this BikeGremlin forum thread:

https://www.bikegremlin.net/threads/vintage-bicycle-frames-with-modern-parts-article-comments.152/

i ride a cromemoly steel bicycle made in 1992,trek racer .this bike never lets me down and i like the fact its very easy to customise and repair when things do wear out,another reason i like the older bikes is they look nicer when rebuilt,they are also made for taller or shorter riders.these bikes are basically fail proof.they are abit heavier than a modern racer but not by alot if you rebuild them with some modern parts and wheels.i wish they still made these bikes brand new as i would buy six more.they are getting harder to find now,especially one that has been looked after.

its sad to see the way the bicycle industry is now going,very expensive bicycles that are just too hard too expensive to fix,carbon fibre bikes are fine for race day but for the average rider they are a poor choice,bicycles were allways meant to be a cheap form of transport and they were allways built so the average person could fix them thats why we bought bikes in the first place,modern bikes dont even fit taller riders,some companies are now making retro style bikes with chromemoly frames but they are rare,i think the bike industry is going down the wrong path,they made chromemoly frames for many years as that system worked very well and it was a fail proof system and you could buy any size bicycle.

Exactly my thoughts, Mike! I’ve gathered near ten old bikes from mostly 80’s and 90’s, some of them later too, but quite basic and simple in their category, nothing too fancy or fragile. They’re are quite maintainable still, some issues here and there, but very little critical ones. I’ve talked with some bike repair people, or more likely fantasized about a “standard bike”, instead of these modern increasingly disposable ones. Frames could be of many shapes and sizes but the critical components would be of old and proven standards that every “standard bike” would share, be it headset, bottom bracket spindle, drop outs, wheels, hubs, axles, brake mounts on the frames, seat post diameter, etc, etc, so that there wouldn’t be any problems in getting those parts and mixing and matching them to your like and make the bike go as great as new for years and years to come. But is there business in it is another question. Bicycle industry is more and more and honestly has for decades been one “the latest hype” driven industry that is in constant vicious cycle (pun intended) of re-inventing the wheel to make the sales soar each year over and over again. I wish there were courageous entrepreneurs that would defy the bicycle industry trends and settle to making a truly “honest” bike, no tricks in order to build proprietary and exclusive non-standard components and other solutions to undermine any competition and consumers rights (think about the derailleur hanger mess for one example, this day and age will leave behind a trail of bicycle frames good only for single speed or internal gear hubs if even that, because of the constant flow of hub width/axle standards). Bicycles should be made for long lifespans, even decades long, if not even century, because the frame, if properly made won’t wear that bad, but the moving parts will and they only need replacement in most cases. That’s my two cents on the topic anyway.

If the worst should happen and the BB-shell threads are stripped from a vintage steel frame, is there any known cure that would actually work in this case? Our LBS’s don’t do metal work so much, they can do light tapping for the threads to clean them, but can’t reverse any damage by much serious means. I got a repair BB from one of the shops, but it lasted less than 50km before the left side cup would cut into two pieces, just like that.

The frame is a mid 80’s Peugeot of 103 Carbolite tubes (comfortably with French metric 35x1mm thread and a noob didn’t know how to detect such an old oddity, even got some helping hand from a strong young man who would ram a steel bottom bracket of ISO standard 34,8×1,06mm thread into that BB-shell. The JIS BB would seem ok there for quite a while, thousands of kilometers even, until the crossed thread would start giving up making tightening the BB not very reliable.

To summarize the question, is there any possible way that doesn’t involve major metal works, like replacing the BB-shell altogether or boring the existing one and sleeving it for all new threads, something that would actually work to get the BB-shell fixed and BB stay? Or am I watching a nice piece of scrap metal in that beautiful frame? Any know cases where stripped BB-shell threads frame has resurrected into its new glory without rebuilding the whole frame?

I know chances are slim by what information I’ve found in internet, but if anybody could even confirm that all repair bottom brackets are waste of time and money or if chemical metal (aka metal particles enhanced epoxy) could be threaded with some odds to make it work for at least sometime in order to have time to find a replacement frame.

Fortunately it’s not my only bike, but very dear to me, like said and would deserve plenty of more fun and enjoyable kilometers.

It should say (comfortably flexing) about the frame, editing got interrupted there. OP

Hi Relja,whats your opinion on fixing up an older 27 inch wheel bike,are they worth messing around with as 27 inch wheels are getting rare these days,I do know that you could possibly run new 700c wheels but how do you find such long brakes,what is the best solution to get an older 27 inch bike running again,i just found a custom built 27 inch bike in the dumpster all original including original rust but this old bike is a hand built lugged frame custom bike and i dont want to see it sitting doing nothing,it is a signature rare bike.cheers

Hi Mike,

It’s still possible to find decent quality longer reach brakes on the used (2nd hand) market.

Modern ones, with a long reach, are still being manufactured by Shimano and others, though I’m not a fan of those

(why I don’t like modern brakes).

So my choice is usually to go with a currently very common 622 mm (28″) wheel size. This makes it easy to source rims and tyres.

back in the good old days Relja when you only rode about 500 miles and you had to replace those cotterpins on a very heavy old steel bike,you simply punched out the cotter pins,hammered new ones in and rode again,none of those cotterpins lasted very long,neither did those caliper brakes,many folk used to convert those old 5 speed bikes and throw in a sturmey archer 3 speed wheel with the steel brake attatched to the frame,then they ran trouble free,you only had to change the sturmey archer gear pull every now and then as those allways broke off.or they would convert them to a fixie.

Can I contact admin??

It is important.

Regards.

Hi,

How can I help you?

P.S.

My contact email is listed here:

https://bike.bikegremlin.com/consulting/#3

Relja