This article explains bicycle fork types and basic terms. A separate article explains the names of bicycle fork and headset bearing parts.

TL/DR

In this article, I’ve explained most things related to bicycle fork design, types, brake mounts, etc.

I’ve also discussed the mix-matching in terms of swapping rigid for suspension forks or vice-versa.

My fork & headset article series:

- Bicycle fork models and brake mounts

- Headsets [01] Names of fork and headset parts

- Headsets [02] Important fork, head tube and headset dimensions

- Headsets [03] Headset bearings standards – SHIS

1. What is a bicycle fork?

A bicycle fork is a part of the bicycle on which the front wheel is mounted and which is turned via handlebars in order to steer the bicycle.

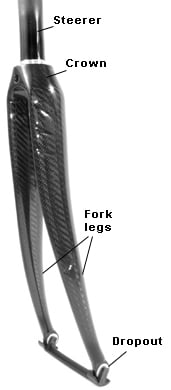

It consists of a steerer tube, crown and fork legs and dropout for receiving wheel axle. It usually has brake mounts as well.

The point where the steerer tube and the crown connect is the point up to which the fork is inside the frame. The part below that intersection is visible.

2. Important dimensions

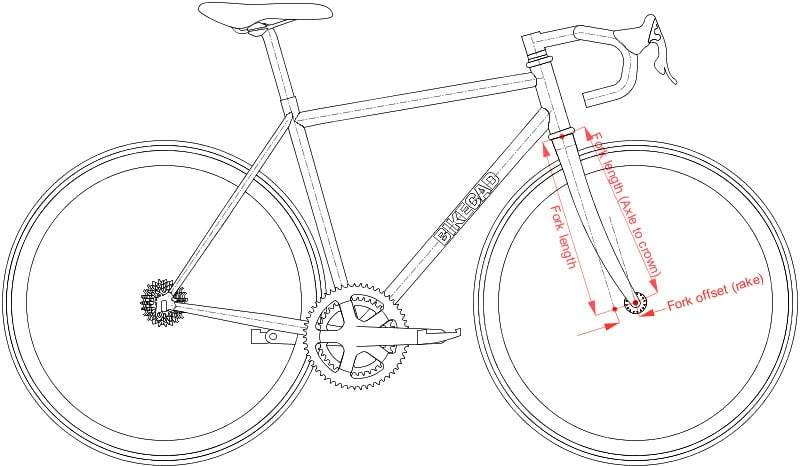

There are three dimensions important when choosing a bicycle fork:

- Steerer tube length – for big frames, or when looking for a more upright seating position, with higher handlebars, it is important to have a long steerer tube.

- Fork legs length, or to be more precise, the length between the crown-steerer intersection, to the dropout. Axle to crown. Important to determine the wheel size which the fork is made for.

- Rake – how far is the axle moved from the steering axis. A picture explains it better:

Rake affects handling, in a way explained in the article about bicycle frame geometry.

3. Types of forks

There are several types of bicycle forks. Two standards of fork attachment, three standards for brake attachment. Also, there are forks with shock absorbers and stiff forks without any springs. So, when choosing a bicycle fork, apart from the size which is needed (kids bike, big bike, MTB etc), it is important to know: how it’s mounted, which brake mounts it has, is it suspension fork.

3.1. Systems of fork attachment

There are two groups of standards:

3.1.1. Threaded forks

It has threads cut into the steerer tube. It is held in place with a nut screwed onto the steerer tube.

The nut is held in place with another nut – locknut.

The advantage of this system is that handlebar height can easily be adjusted – one bolt is unscrewed and the handlebars are moved up and down.

It is inserted into the fork.

It is held in place with a quill system. Fastening the bolt on top moves the quill sideways, pressing it onto the inside walls of the fork.

In case the bolt, or the quill snap, get damaged, the handlebars are free. 🙂

The greatest flaw of this system is that the bars are held in place with a quill and one bolt. In one place. Moisture gets in, it can rust, then it can get stuck. It can also rust a lot and get loose without any warning. The stem is held just at the place of the quill – the top part of the fork just prevents the stem from moving left-right, but it doesn’t hold it tight in place.

3.1.2. Threadless – “ahead” forks

Fork is put into the frame, then stem and spacers are stacked to cover the protruding steering tube. Then at the top there is a cap with a bolt that is fastened to preload steerer bearings. After the preload is set, the fork is held in place by tightening stem bolts – usually two.

This system allows for one bolt to snap and it is all still safe and works well. It also holds the stem much more securely and firmly.

3.2. Brake attachment system

There are three standard systems. Forks usually support one, sometimes two, and very seldom all three brake mounting standards. The standards are:

- Brakes mounted at the centre of the fork

- Brakes mounted on fork leg mounts

- Disc brakes

3.2.1. Brakes mounted at the centre of the fork

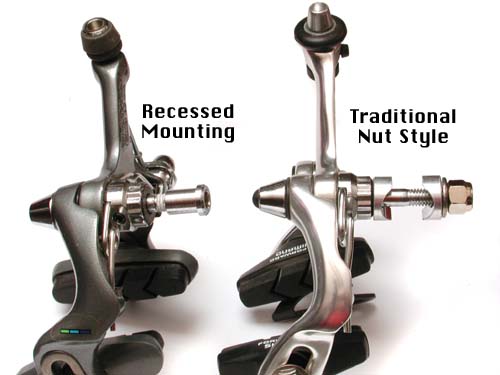

Mounting system popular with older bicycles and (with slight mounting nut variations) with modern road bikes.

Fork compatible with this system has a hole for mounting the brake drilled. Also, the hole is up to 6 cm away from the rim, so that brake calipers can reach the rim.

With this kind of forks, it is important to know for what wheel size they are made. In case a smaller wheel is used, brake calipers might not reach the rim. In case a larger wheel is put, it might not fit at all.

Modern bicycle forks have recessed rear side for nut that holds the calipers to be screwed in, while the old standard is with round rear side. This is important because of brake compatibility:

On the right is the old caliper type, with a longer bolt, and nut fastening on the outside of the fork.

3.2.2. Brakes mounted on fork leg mounts

Brakes are fastened to fork mounts.

Brakes mounted on fork mounts are usually of cantilever, or V-brake type. Cantilever brakes require frame mounted brake cable stops above brake calipers as well as fork mounts (detailed about that in a separate article).

Two pointy axles on which brake calipers are screwed onto.

Many of such forks have a hole drilled in the middle. Through that hole, a bolt can be put for holding mudguard, or for attaching brake mounted at the fork centre.

Here it is also important to make sure that fork is used with appropriate size of wheels. Fork for 28″ wheels can take 26″ wheels, but in that case brakes will be placed too high in that case and won’t be able to catch the rims of the smaller wheel.

3.2.3. Disc brakes

Disc brakes are mounted on the left hand side of the wheels, so the left fork leg has mounts for disc brake caliper fastening.

These forks can also have drilled hole in the middle for “ordinary” brakes, or mudguard mounting. They can also have V-brake mounts.

Here combining different sized wheels is OK, because disc brakes don’t use rims as braking surface. However, using a small fork with too big a wheel can be a problem – it might not fit.

3.3. Suspension vs rigid forks

3.3.1. Rigid forks

Rigid fork concept is clear – metal fork of appropriate length for the wheels it is made for.

3.3.2. Suspension forks

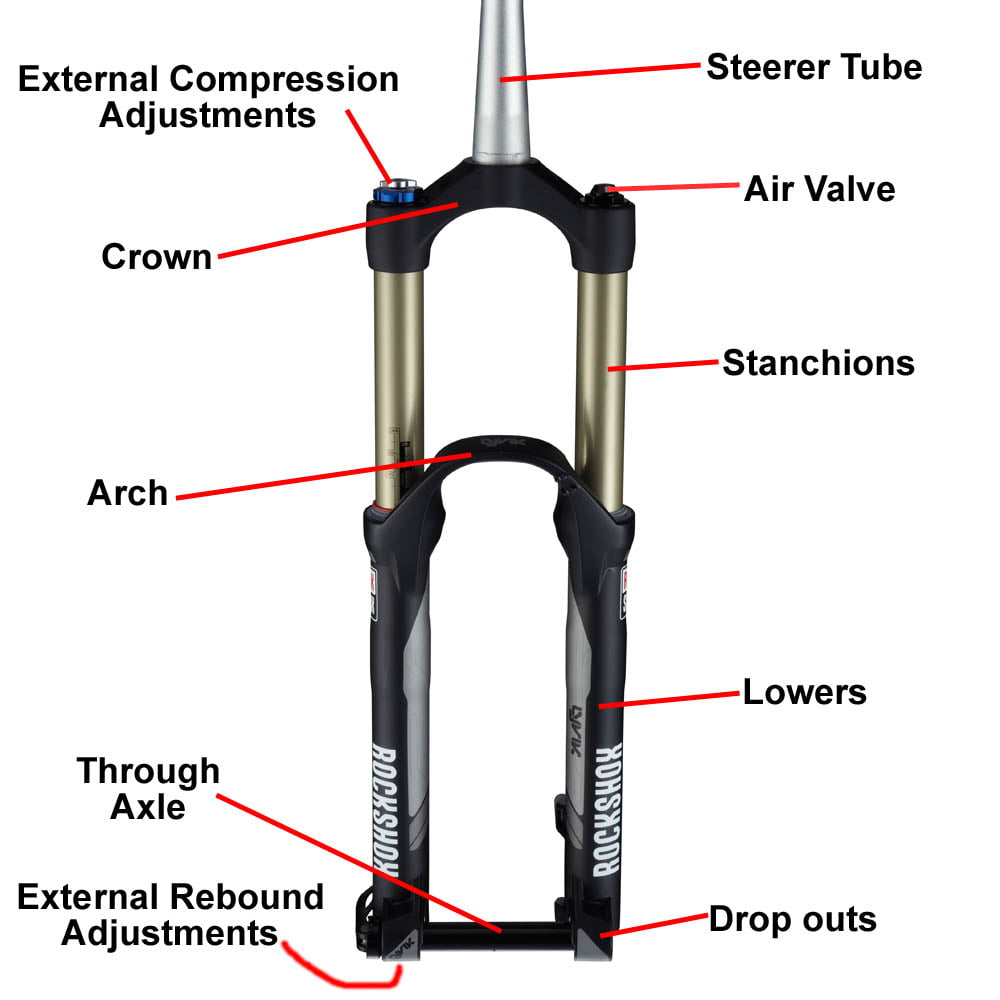

Suspension forks are telescopic forks with a certain amount of travel. Parts of the suspension fork are shown in the picture below:

Detailed explanation of suspension forks is given in the article: Advantages and disadvantages of suspension on bicycles. Here I’ll just mention important attributes, without defining them:

- Amount of fork travel – usually between 6 and 20 cm.

- Possibility of lockout (or lock) – making it behave like a rigid fork – good when climbing hills

- Possibility of adjusting preload, compression damping and rebound rate.

Suspension forks compress when the front wheel hits a bump, then moving slowly back into previous position. They extend to a degree when a wheel reaches a small hole in the road. Doing this, good quality suspension forks improve front wheel traction and make the ride more comfortable.

Theri downside is greater weight and need for maintenance. For most riding conditions and styles, enough dampening can be achieved just using fatter tyres.

3.3.3. Suspension corrected rigid forks

Suspension forks are generally longer than rigid forks. Because of travel, in order to prevent the crown from hitting the tyre, suspension forks need to be longer.

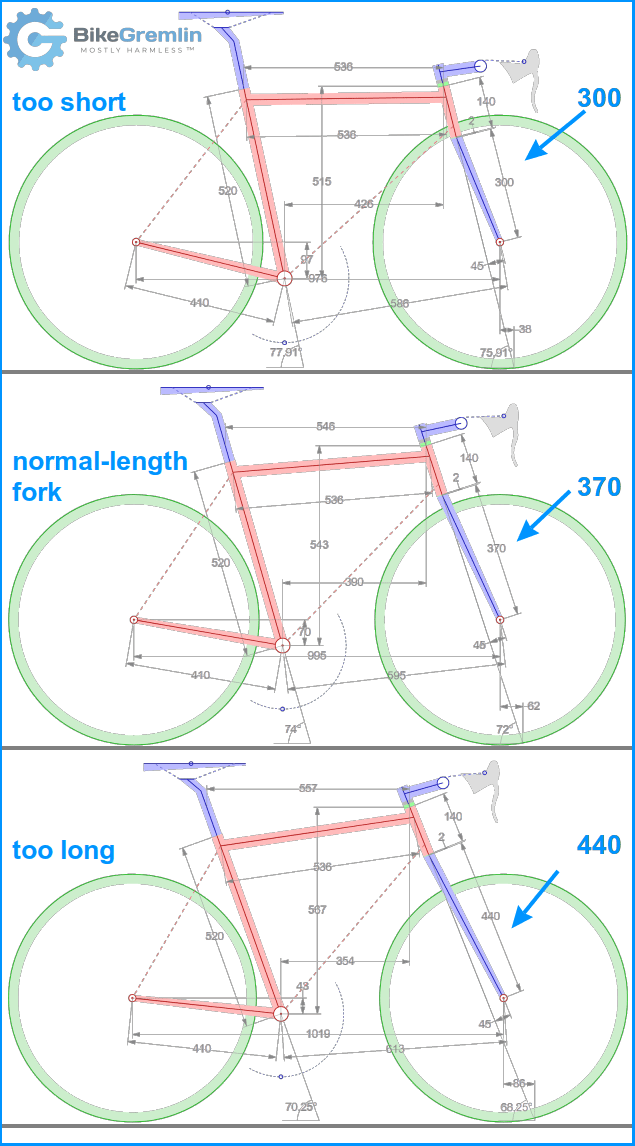

If a bicycle frame is made for (longer) suspension fork, and for any reason, one wants to switch to a rigid fork, regular rigid for will be too short. Too short fork will ruin the bicycle’s frame geometry, making steering too twitchy. That is why suspension corrected rigid forks were introduced. They have axle to crown dimension about 10 cm longer than a standard rigid fork.

In other words, suspension-corrected forks look like regular forks, just fork legs are longer (longer axle-to-crown distance).

For 622 mm sized wheels (28″ and 29″), standard “ordinary” fork axle-to-crown length is from about 37 cm for road bikes with narrow tyres, to about 40 cm for trekking bicycles with wider tyres (up to about 42 cm for frames designed for very wide tyres). Suspension-corrected fork axle-to-crown length ranges from 45 to 50 cm.

These forks are often more expensive and less widely available.

The following picture shows how fork length, whether it’s too short, or too long, affects the entire bicycle frame geometry:

Last updated:

Originally published:

After two days of looking for a detailed explanation of forks and “hangers”, this is the most concise information and best explanation I’ve found anywhere. Really, thank you sincerely