I already wrote about the modern hookless rims (for tubeless tyres). In this article, I’ll explain what tubeless bicycle tyres are, and list their pros and cons compared to tyres with a tube. Based on that, everyone will decide for themselves which option is better suited for their needs (in other words, answering the question I often get: “should I switch to tubeless?”). To make this article clear even to absolute beginners, I will start by briefly explaining the basics and tyres with tubes, before explaining the tubeless tyres.

Table Of Contents (T.O.C.):

- Why do tyres have air inside?

- Tyres with tubes

- What are tubeless tyres?

- Pros and cons of tubeless tyres

1. Why do tyres have air inside?

Tyres with air are so common, that it may seem silly, but let us entertain this question for a bit. We all know that tyres filled with air can be punctured (flat), so why do we use them? Why don’t we use just some soft rubber or some springs coated with rubber tread?

In fact, every few years I run across some startup project promising just such “revolutionary, flat-free tyres!” How come no one has thought of that before?! Except that they have – airless tyres is what we had started with in the first place until a crazy Scotsman John Boyd Dunlop patented pneumatic tyres and put them on market around 1846.

Why is the air in tyres a phenomenal thing, despite occasional flats? Because it makes the tyres lighter, comfier, and with lower rolling resistance.

To further explain: air is light, which reduces the total wheel mass, and it is an excellent bump absorber. It compresses and expands easily, with practically no heat build-up, and it distributes compression pressure equally along the entire tyre (inner) surface. This allows tyres to grip better (as their contact patch easily conforms to any terrain irregularities in no time) and absorb smaller bump and pothole shocks.

2. Tyres with tubes

For over a century, the standard for bicycles were tyres with tubes. You mount a tyre (outer one, with a tread) on the rim, and a tube for holding air is put inside.

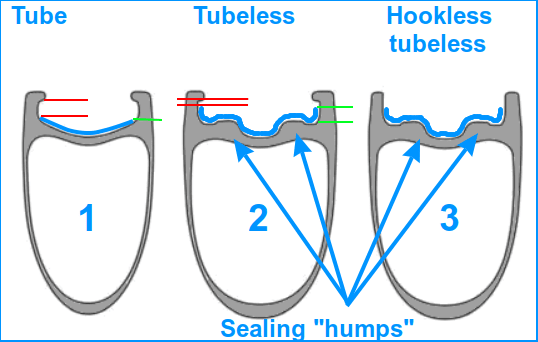

Picture 1

Separate articles explain:

Thanks to bicycle tyres being quite flexible and light, it is quick and easy to dismount a tyre, patch a tube, and re-mount it all (unlike it’s the case with heavy and rigid car and motorcycle tyres).

The main downside of this patent is that tubes can be punctured if you run tyres at a lower pressure and hit a bump. When the outer’s tyres tread is compressed all the way to the rim, it pinches the tube and tears it against the rim, creating two holes next to each other (tearing it against the right and left rim wall). This is called a pinch flat. On narrow road bike rims, these holes are too close to each other to fit two separate patches, and too far apart to be covered well with one patch – so it’s generally irreparable damage. Because of the distinct look, this kind of puncture is also called a “snakebite” flat.

Picture 2

Now, why would you ride with low tyre pressure? When riding on mud, sand or snow, the grip is much better if the tyres are wider, and inflated to lower pressure. But then you must slow down when approaching a bump, so you don’t hit it hard and puncture your tube. Is there an alternative solution? A logical question which leads us to the next chapter:

3. What are tubeless tyres?

Tubeless bicycle tyres are constructed so they can keep air under pressure without any help from a tube. To achieve that, they need to fit tightly against the rim – so they are made with a bit thicker and stiffer sidewalls compared to non-tubeless tyres. This makes them a bit heavier, but “ordinary” tyres need a tube, and a non-tubeless tyre plus a tube usually ends up being a little bit heavier in total compared to a tubeless tyre plus sealant liquid (more on that below).

Of course, the rim too must be constructed to hold air – so that the entire “package” can effectively replace the tube. Tubeless rims don’t have any spoke holes on their outer section (the one where the tyre is mounted), so are a hassle to build wheels with and often require special & expensive nipples. Tubeless-ready rims, on the other hand, are more like the normal rims, but they have a “hump” to help seal the air with a special tubeless rim tape.

Picture 3

In a separate article, I wrote about modern hookless rims for tubeless tyres.

Tubeless bicycle tyres are still a lot more flexible than motorcycle tubeless tyres – we can’t afford tyres that weigh several kilograms on a bicycle. That’s why they can’t fit against the rim tightly enough, so we must use sealant fluid in order to keep the wheels airtight.

The liquid is poured directly into the tyre when mounting it, or after it has been mounted through the valve (after the valve core has been unscrewed and removed). A separate article explains bicycle valve types.

The sealant liquid is a fluid, containing latex or carbon fibres, which hardens when it comes in contact with the outer atmosphere. This enables “self-sealing” of smaller punctures, but if you park the bike so that the valves are at the bottom, the sealant can harden and clog up the valves, preventing you from inflating your tyres.

Also, the liquid needs to be replaced regularly – every six months, to a year max. Latex-based sealants will harden after a year or two even inside their original, sealed bottle.

4. Pros and cons of tubeless tyres

Here I will list all the tubeless tyre pros and cons, leaving it to the readers to decide how much each of those is important for their use case, and decide what the optimal choice is. The comparison is made against the “ordinary” (non-tubeless) tyres of the same dimension and quality (class).

Tubeless tyre pros

- Lower total wheel mass, though the difference is marginal when you account for the sealant liquid mass (also, see the “Rotating mass myth” article).

- Smaller punctures will self-seal thanks to the sealant liquid.

- They let you ride with lower tyre pressure, without the risk of pinch flats (“snakebites”).

- Slightly lower rolling resistance, because there’s no rubbing of the tyre against the tube (as there is no tube, obviously 🙂 ).

Tubeless tyre cons

- More difficult to mount on a rim due to stiffer sidewalls.

- More complicated to mount – because there is no tube to hold air from the start, you must use an air compressor (or a CO2 cartridge) to pump a lot of air very quickly, so the tyre gets pushed against the rim walls to seal before a lot of air goes out. You also need to add sealant, not too little, not too much, taking care not to make a mess.

- Larger punctures won’t self-seal, but the sealant will leak out and make a mess. Yes, there are tools for quick patching of tubeless tyres (Amazon affiliate link – don’t rely on its frame mount, carry the tool in a bag), large enough punctures still require mounting a tube to get home (after removing the tubeless valve from the rim).

- If you dent a rim, the tyre will start losing air – you must either insert a tube, straighten the rim somehow, or carry the bike home (pushing a bike with a flat tyre can cause tyre sidewalls to crack, ruining it).

- You must regularly top up and replace the sealant liquid, taking care it doesn’t clog up the valve (park the bike with the valve staying up, not near the ground).

- Tyre under low pressure can relatively easily become unseated from the rim in one spot when you hit a bump or put some sideways force on it (like landing a bit sideways from a jump or similar). When that happens, the tyre loses more pressure (that’s called “a burp“). So you need to stop and re-inflate the tyre.

I think that tubeless tyres make some sense for mountain bikes (MTB) ridden on challenging terrain (rocks, mud, sand, snow etc.) because they can be run at lower pressures without any pinch-flat risks. Also, because they can “self-seal,” they make some sense if you ride on thorn-ridden terrains, and you don’t like the rougher ride and more weight of (non-tubeless) tyres with serious puncture protection (like Schwalbe Marathon – Amazon affiliate link).

While they are advertised as “new, improved, better” – tubeless tyres have their cons and I personally still highly prefer the ease, simplicity, and reliability of hoked rims with clincher tyres and tubes. Your preference may differ.

ok back to the future,check out these simply awesome presta only all metal chucks that can connect to just about any pump hose,they are hiro pista and harame chucks,not cheap but very nice ones,can do well over 200 psi and replacements parts are there as well around $100 per chuck but a good investment for your workshop if you do alot of presta valve pumping